As I near the end of my wordless picture book, I decided to shorten it from ten pages to eight. This change wasn’t just about simplification; it helped me focus on the story’s core message of stewardship. Each page now carries intention, leading the reader through a cycle of taking, using, giving, and renewing.

Learning Goals:

I completed pages 6–8 and found that they bring the story full circle. The barn stands complete, animals thrive, and the once-felled tree continues through the structure and nearby saplings. The visual message becomes clear, humans can take from nature responsibly and give back intentionally, restoring balance. Shortening the book also mirrored the theme of sustainability, removing excess, keeping what’s essential, and creating space for renewal.

What I did/Evidence of Learning:

I completed rough sketches for the final pages:

- Page 6: The barn finished, glowing with warm yellows and oranges. Animals and a harvest begin to enter the scene.

- Page 7: Children and farmers plant and tend to saplings growing near the stump. Flock of birds returning.

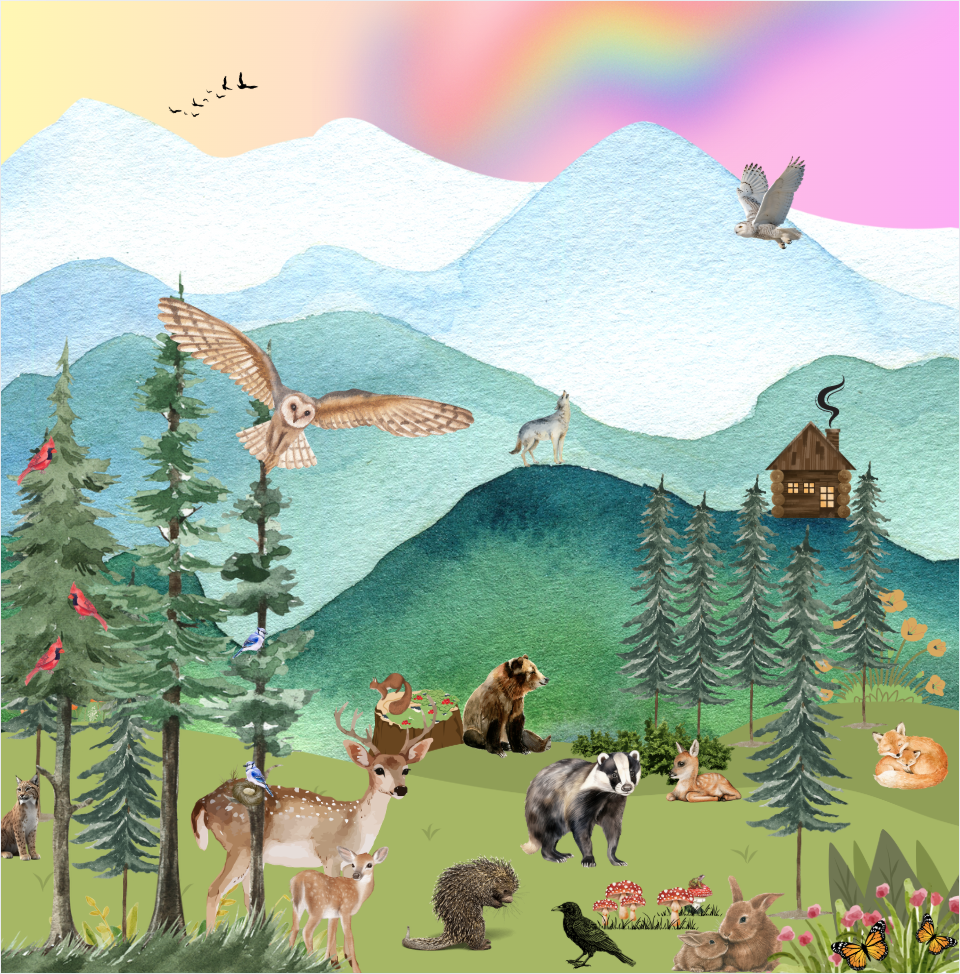

- Page 8: Wide, bright scene, showing forest, house, wildlife returning in abundance, and a balanced ecosystem.

This stage of the project helped me conceptualize how visual storytelling can model stewardship. Even without words, images can teach children that we are part of an interconnected garden of life and responsibility.

Connection to Inquiry and Learning

To deepen my understanding of stewardship in a BC context, I explored several online resources such as visual archives, environmental education sites, and virtual maps of BC forests.

Engaging with BC stewardship programs, such as Islands Trust Stewardship Education and the Green Shores training modules from the Stewardship Centre for BC, allowed me to connect my creative choices to real-world practices and understand how stewardship is enacted in communities.

Coastal and island communities in BC are actively learning to protect habitat, restore natural shorelines, and balance human needs with ecological health. Seeing this real-world stewardship reminded me that the barn and forest scenes in my story aren’t just symbolic, they reflect practices that communities are already doing. It encouraged me to make those scenes more specific and meaningful.

Linking my work to the First Peoples Principles of Learning reminded me that storytelling is relational, it connects us to land, community, and future generations. As a future teacher, this makes me think about how I want to design learning experiences for my students. I hope to create activities and stories that help children notice the impact of their choices, care for their environment, and understand their place within a larger community.

Learning is holistic and relational → The story shows the connections between people, animals, and the land.

Learning recognizes responsibility to the land → The tree’s transformation and renewal reflect respectful use of natural resources.

Learning involves patience and time → The slow, reflective creation process mirrors this principle.

Learning is embedded in memory, history, and story → The book itself becomes a story of renewal and care for the earth.

Learning involves generational roles and responsibilities → Sharing the book with my daughter reflects learning across generations.

Together, these resources strengthened my understanding that digital tools, workshops, and educational programs can extend relational learning, helping us explore, share, and model respect and care for the environment.

Reflection:

Simplifying the book reinforced for me that teaching stewardship is really about restraint, awareness, and respect. Every choice I made, what I included and what I removed, felt meaningful, just like the decisions humans make with the land. Seeing these lessons come alive through my own book has made me more aware of how powerful visual storytelling can be in shaping understanding and values.

Next Steps:

Next, I will review the full eight-page draft with my daughter, gathering her perspective as a child reader to see if the story’s message of care, renewal, and gratitude for the land comes through clearly. I’ll then revise as needed before final edits and creating my artifact.